Great Maps

Ordnance Survey maps are a unique British treasure. We chat to Rob Andrews from the OS about its history, aims and legacy.

Ordnance Survey maps are as British as Yorkshire tea. Rich in detail and description, the maps are used by explorers and couch potatoes alike. A national treasure that traces its origins back to the 18th century, Rob Andrews from the OS talks about the origins and affectation we feel for one of Great Britains’ longest running institutions.

Tell us about the origins of the Ordnance Survey.

The OS has its roots in military strategy, first mapping the Scottish Highlands following the rebellion in 1745. Later, as the French Revolution rumbled on the other side of the English Channel, there were real fears the bloodshed might sweep across to our shores. So the government ordered its defence ministry of the time – the Board of Ordnance – to begin a survey of England’s vulnerable southern coasts. Until then, maps had lacked the detail required for moving troops and planning campaigns.

Early maps were originally created by surveying parties using simple compasses to measure the angles, and chains up to 50 feet long to measure distance between important features. Much of the rest was sketched in by eye. However, in 1784 Jesse Ramsden, the leading instrument maker of the day, designed a spectacular theodolite (a precision instrument for measuring angles horizontally and vertically) that took three years to make and measured three feet across. Using Ramsden trigonometry and the theodolite, a sophisticated network of accurately measured triangles became the basis for the maps we still use today.

How do you keep the maps up to date?

OS maintains a National Geographic Database of over half a billion features from detailed road and buildings to footpaths and cycleways. This data is relied upon by government, business – from start-ups to huge organisations – and individuals and outdoor enthusiasts. OS has a team of 200 surveyors who make roughly 20,000 changes to the mapping database every single day.

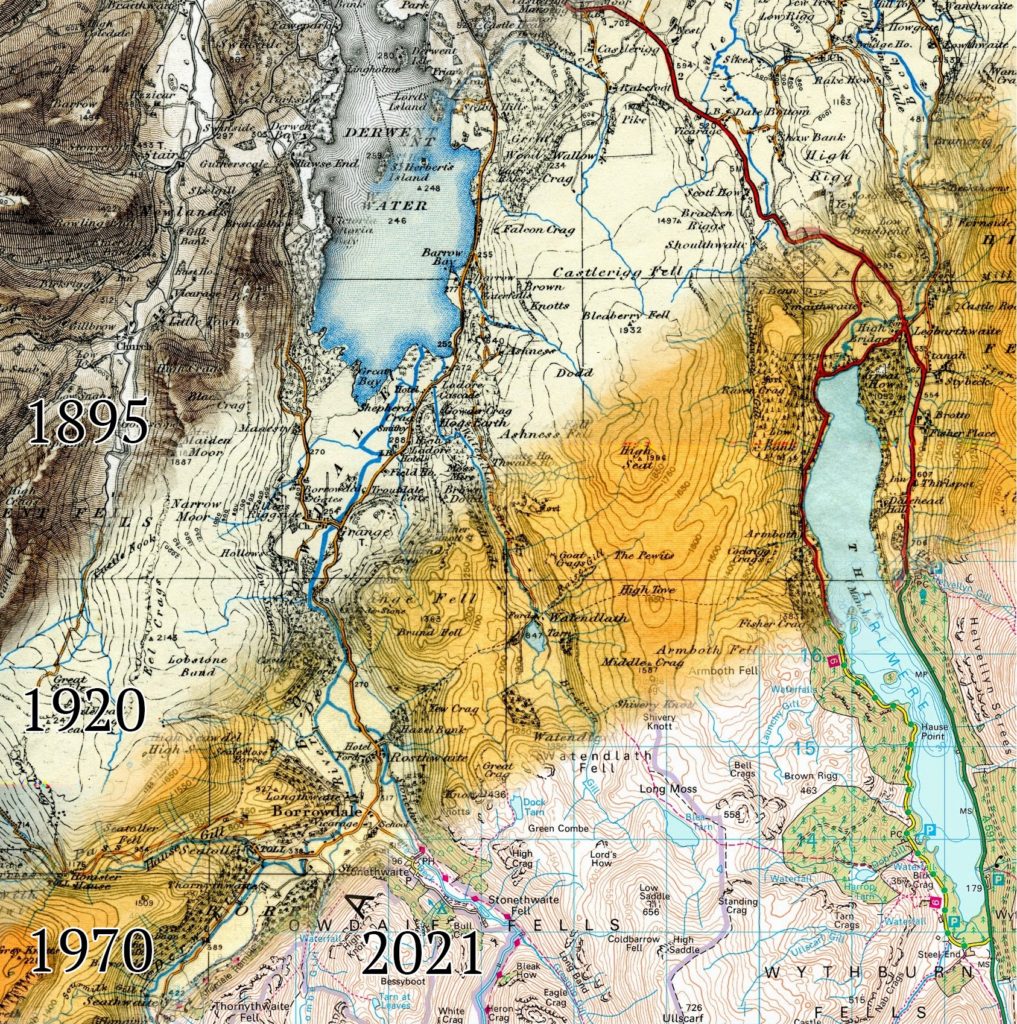

The physical paper maps, OS Explorer Maps and OS Landranger Maps, are updated periodically depending on the volume of change in the area. This can range from every two years up to seven years.

How is the information collected?

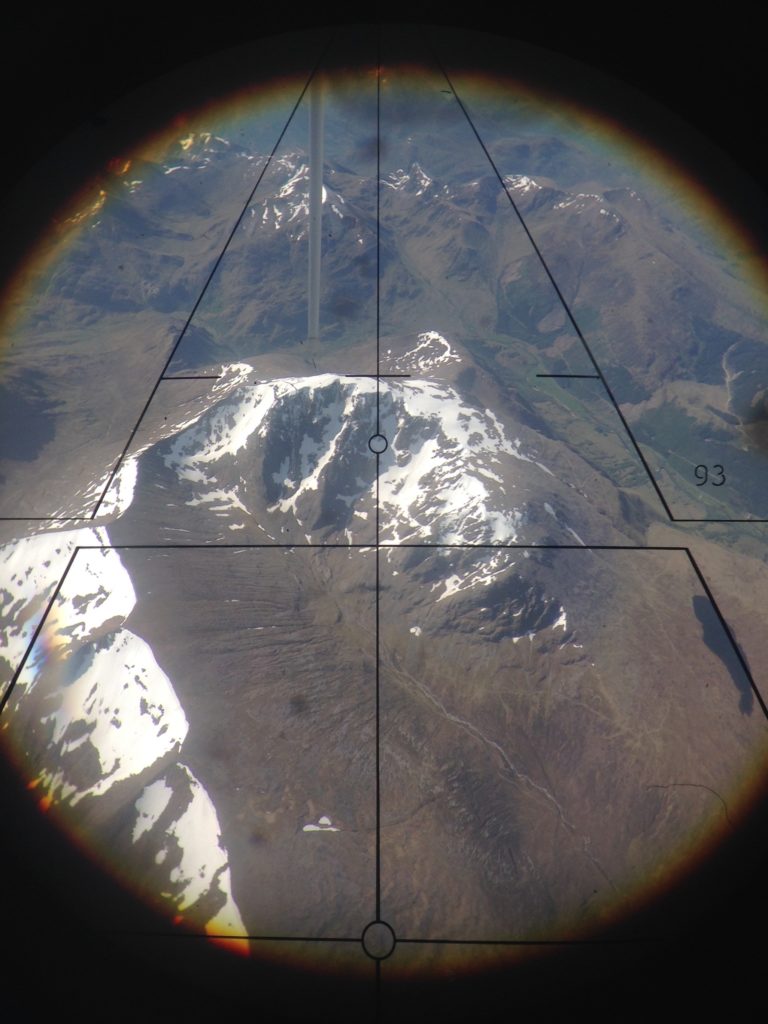

200 surveyors, two aircrafts, and an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) team work to keep the database up to date (20,000 changes a day). The Flying Unit map Great Britain from the skies, flying around 100,000 km a year. Some data comes from satellite images. Surveyors use OS Net and Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) technology every day to instantly position new map detail to within a few centimetres. While you might find the old stone Trig pillars dotted around the landscape, they’re no longer used.

What role does the OS play in everyday life?

OS is typically recognised as ‘the paper map people,’ but the Leisure part of OS serves as less than 10% of the overall business. It’s still an important element, but we also support government, businesses and everyday lives. Recent research showed that on an average day, users will make use of OS data 42 times. That can be anything, from utilities, administrative boundaries, flood risks, deliveries, mobile phones, getting from A to B, or getting outside to explore. OS deals in location, and everything happens somewhere.

Are you moving from paper to digital?

Paper maps are still important to OS, they’re not going anywhere. We produce around two million maps a year and even offer a custom-made map option to allow customers to centre a map on any location and then add own their map cover title and image. There’ll always be ramblers, hikers, hobbyists and even collectors – a detailed map is a beautiful thing to own and a useful back-up if you lose service or battery life on your mobile app.

Do you think OS gives people the confidence to explore the countryside?

OS love that they help millions of people get outside and explore Great Britain every year. Particularly around the COVID-19 lockdowns, we saw a huge uptake in people using the maps, relying on the data to explore from their front doors and local neighbourhoods. We want to encourage a love and respect of the outdoors to encourage people to maintain areas of natural beauty and protected sites so other users can explore and enjoy them in the years to come. Leave no litter or damage behind; just footprints!

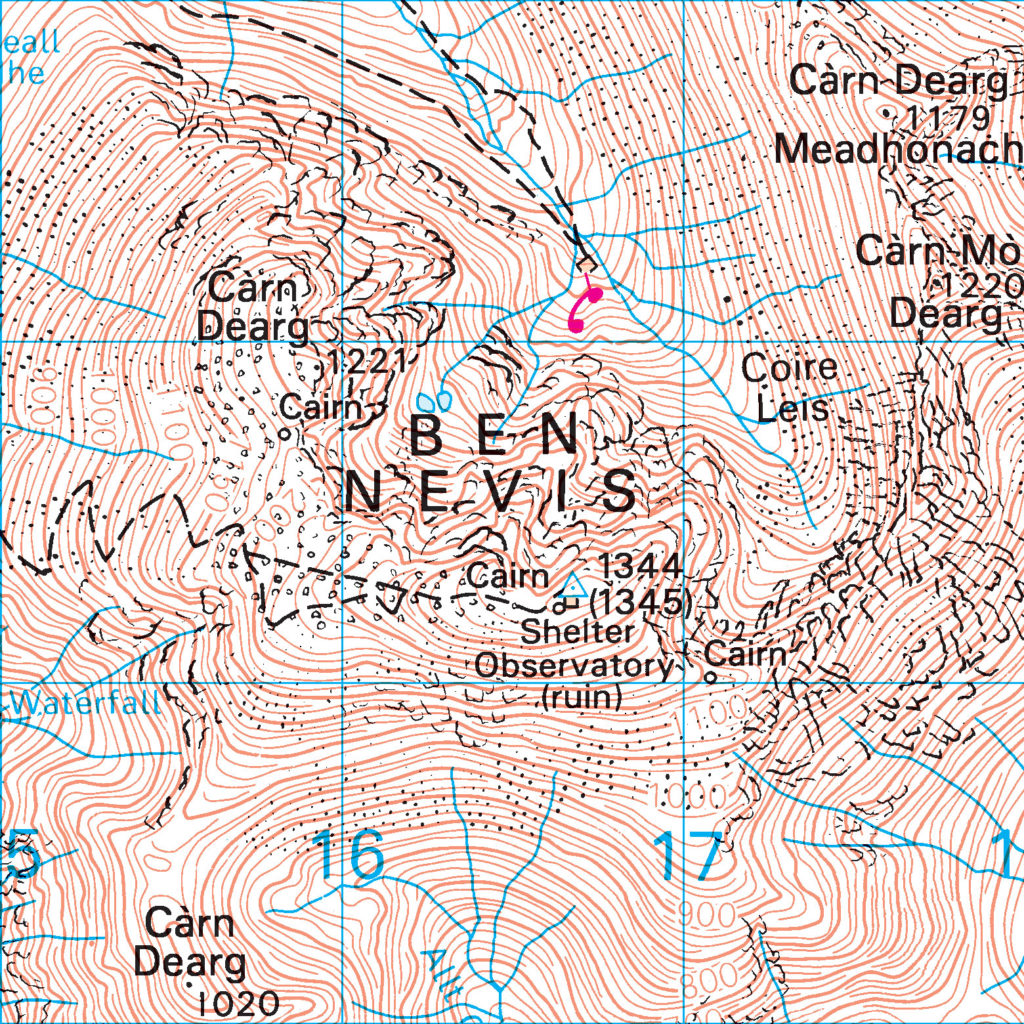

And finally, a little postscript and ode to the OS from Bill Bryson’s book, Notes from a Small Island

“As a rule, I am not terribly comfortable with any map that doesn’t have a You-Are-Here arrow on it somewhere, but the Ordnance Survey maps are in a league of their own. Coming from a country where mapmakers tend to exclude any landscape feature smaller than, say, Pikes Peak, I am constantly impressed by the richness of detail on the OS 1:25,000 series. They include every wrinkle and divot of the landscape, every barn, milestone, wind pump and tumulus. They distinguish between sand pits and gravel pits and between power lines strung from pylons and power lines strung from poles. This one even included the stone seat on which I sat now. It astounds me to be able to look at a map and know to the square metre where my buttocks are deployed.”